Fittingly, the story ends in Cumberland Cemetery, the final resting place for many Pratts, Painters, Tylers, Worralls, and Darlingtons, where individual women and men were (more than in life) equally recognized, their families around them, their gravestones affirming eternal life. Minshall Painter recorded in 1859 that Thomas Pratt was “laying out a piece of ground for a cemetery” alongside the Friends’ graveyard, and by the end of 1860 the Delaware County American acknowledged its operation with the notice of Elizabeth Sill’s funeral procession from Edgmont “to Cumberland Cemetery, Middletown.”84 The name “Cumberland,” as a map of original land grants from William Penn shows, had been associated with this property since the seventeenth century. Claiming it through his wife Mary’s inheritance, however, Thomas Pratt used the name of a county in northern England for a new purpose. This was not a Friends’ burial ground, nor attached to any other church affiliation or township. It was a place of rural peace, without denominational ties and open to any who cared to buy into it.85

Buying remained an important aspect of the arrangement. By no means an enclave only of the wealthy, it was also not for the poor or the anonymous stranger. Nor do we have any evidence that the blacks in Lima or the mill workers of Rockdale were represented at Cumberland. The Honeycomb United African American Church on Barren Road and the evangelical churches of the lower Chester Creek served those communities in life and death. Cumberland was primarily for the white Protestant middle class residents of the region.

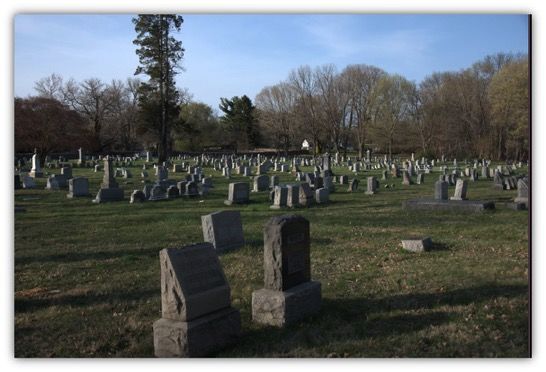

The cemetery has proven a good neighbor to students from Penn State Brandywine. Graveyard studies are a thriving branch of interdisciplinary American Studies, embracing art, archaeology, religion, and social history; students of Phyllis Cole and Laura Guertin have looked with care at its tombstone weathering rates, its representations of gender and social status, and its changes from the mid-nineteenth century through the twentieth. Nor does the place stand alone: the lives memorialized in it extend outward to Minshall Painter’s journalizing about them, to an official “Interment Journal” that lists home towns and causes of death for those buried from 1885 on, and to the newspapers and public records that tell more of individuals named on these stones. As Eileen Fresta writes in her senior honors thesis, work developed through both Cole and Guertin, Cumberland Cemetery is “alive with history,” itself a historic landmark and a key to the society and culture beyond it.86

In particular, Cumberland is in its origins a modest contribution to the “rural cemetery” movement of nineteenth-century America. Like its much larger predecessor in Philadelphia, Laurel Hill, Cumberland was open to “lay expressions of the meaning of death” because of its separation from particular churches.87 Look over the stone wall dividing it from the original Quaker burial ground to see the difference. From the early eighteenth century, approximately 1200 people had been interred by the Quakers in very small space and in the order of their deaths; a written record was kept, but grave markers were considered worldly ostentation, and only in the nineteenth century would even the smallest stone markers with names and life dates be allowed to remember the dead. The Painter brothers’ regret that their mother had no memorial but the magnolia tree they planted is one sign of discontent with such communal and self-effacing customs. On the other side of the wall Minshall and Jacob purchased lots for their own elaborate mausoleums, which declared to the world who they were and what they had stood for, amidst carved emblems of the nature they revered. All around them in this oldest (northern) part of Cumberland are more modest grave-markers, including Thomas and Mary Worrall Pratt’s, often with Quaker dating (“tenth month” instead of October) that reveals their origins. But even these are larger and taller than the humble markers next door, and some stones even combine Quaker dating with decorative Victorian carving. Choice was actively encouraged, individuality and family affiliation affirmed.88 Graves were set in a garden-like space, so that family members might visit and pay their respects to the dead. A direct descendant of Thomas and Mary Pratt, Betty Ann Hadley, reports that in childhood she would join her relatives in visiting Cumberland to care for the family graves, and she enjoyed running around on its “spit-spat” grass and gravel pathways.89 Rural cemeteries were for the living as well as the dead.

Walking among the gravestones of Cumberland allows visitors even now to survey the choices that surviving family members once made. In the oldest part of the cemetery, open areas suggest that not all grave sites were marked in any way; a ground-penetrating radar study shows more than a hundred unmarked burials, at least some of them influenced by the old Quaker custom.90 On the other hand, the status and wealth of individual families are openly declared through fenced enclosures, imposing obelisks, and mausoleums like the Painters’; at the southern end of the cemetery, their nephew John J. Tyler is memorialized in one even more imposing, if less ornate. Gravestone art and poetry openly lament the deceased and declare them partakers of heavenly immortality; Victorian optimism and sentiment prevail over older cemetery images of death and divine judgment. Among the symbols carved in rock at Cumberland are a willow tree for mourning; a broken chain, plucked rose, and hourglass for mortality; an upward-pointing hand, lily, or evergreen bough for the heavenly afterlife; and crosses for mainstream (non-Quaker) Christian church members. Words add to visual emblems, whether original or provided by the hired gravestone artist. “No night in heaven,” one epitaph simply declares in 1888. A year earlier, another addresses a more poignant message to the deceased woman of thirty five: “Thy hands are clasped upon thy breast/ We have kissed thy lovely brow/ And in our aching hearts we know/ We have no mother now.”91

Cumberland served Quakers, ex-Quakers, members of other denominations, and non-believers like. The same might be said of other Philadelphia-area cemeteries—like Laurel Hill, whose guidebook declared it a place where “all parties can meet in forgiveness and harmony.” But Cumberland is especially evocative of harmony in extending literally from the property of the Hicksite meetinghouse to the property of the Orthodox meetinghouse. We do not know how many Orthodox actually chose Cumberland; eventually they had their own burial ground too. But in design it provides a bridge or at least a buffer zone between the separated Quaker communities.92 Thomas Pratt offered no statement of intent, but let the landscape speak for itself.

After Pratt’s death, Cumberland also became an incorporated business of more explicit design and outreach to the public. The origins of this shift lay in his own contested ownership of the land—a conflict about which there had apparently never been any resolution or forgiveness. When he willed all his land holdings to his second wife, Sarah Johnson Pratt, the children of his first marriage sued to regain their mother’s land and capital. Though they won much of it back, Sarah retained the cemetery land, which she then sold by auction to pay other debts of the estate. As the Chester Times put it, a “syndicate of gentlemen” bought these seventy acres in 1885, and soon they were advertising “A New Place of Burial” called Cumberland Cemetery.93 One of the gentlemen, James Smith, became its superintendent, living for more than twenty years in the new Gothic-style cottage by its gated entrance. As incorporated by this group and carried out by Smith, the cemetery now required a detailed “interment journal” keeping track of burials and causes of death, and the cemetery itself adhered substantially to a more geometric plan known as “Lawn Park” style. The individualistic gravestone art of the rural cemetery was regulated, and perpetual care made family maintenance of graves unnecessary. Or at least that was the apparent intention. In fact Eileen Fresta concludes that Cumberland in the later nineteenth century was a “crossroads” of rural and Lawn Park style, with large monuments and gated plots still permitted.94 Both the inscriptions quoted above (from the 1880s) and the Pratts’ reported custom of maintaining their own family plots (well into the twentieth century) were part of the older way.

Cumberland Cemetery's superintendent's cottage

Cumberland Cemetery, especially in the context of its lists and documents, is a rich resource for understanding this region, offering both an aggregate of human information and a key to individual lives. The Interment Journal lists 2261 burials from the 1890s through 1980s, and the gravestones add many hundreds of earlier burials to the total. In the 1930s the Works Progress Administration listed all the readable grave sites by name and number, providing a baseline for comparison with what we can see now.95 And these thousands of human cases connect with records contemporary to their own lifetimes. Minshall Painter proved true to his indefatigable habit of record-keeping with a journal called “Necrology,” commenting on particular deaths in his time and place.96 The county’s archive of wills and property records, as well as searchable websites, offer access to family records and contemporary newspapers. Here we can sample only a few of the conclusions that American Studies students at Brandywine have reached in their scrutiny of these materials.

Those buried at Cumberland are not just from the Middletown neighborhood, but from an area extending throughout the region, from Chester to Philadelphia to Kennett Square. As Eileen Fresta discovered under the guidance of Dr. Laura Guertin, over the decades covered by the Interment Journal average life expectancy rose from 40.55 years in the 1890s to 75.9 years in the 1980s, numbers corresponding roughly to those of the US Census Bureau and skewed by the larger number of childhood deaths in early years. A charting of causes of death reflects the near-disappearance of tuberculosis and diphtheria over these decades and rising rates of cancer and heart disease.97 The use of gendered family titles was the focus of research by a group of Guertin’s students: surveying 269 gravestones of men and 229 of women, they discovered that while only 18% designate the male deceased as “Husband,” 49% designate females as“Wife”; on the other hand, 47% of the men are called “Father” and only 37% of the women “Mother.” The marital bond is apparently considered the dominant identification of a woman, whereas parenthood stood first for men.98

Cumberland Cemetery

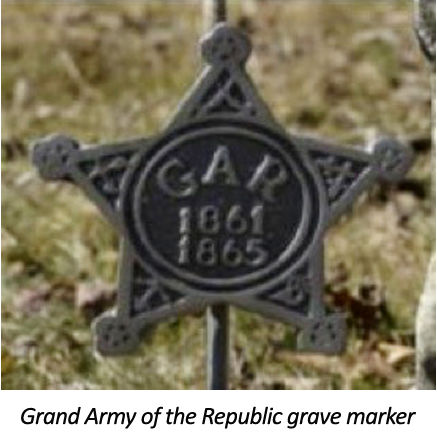

American war service is reflected throughout the cemetery’s existence: records at the Delaware County Archive confirm the graves of 106 Civil War veterans buried at Cumberland, along with veterans of the Spanish American War, World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War. The graves of many Civil War soldiers are marked “GAR,” noting their part in the “Grand Army of the Republic.” Among them we have also glimpsed individual characters. Minshall Painter’s “Necrology” tells of Richard Passmore, who died in 1863 after being “taken prisoner by the Rebels and taken to Richmond…where it is represented he was severely used,” dying from abuse and starvation despite a prisoner exchange.99 Others returned home and had long post-war lives, three of which were researched as case studies by individuals in Cole’s 2003 American Studies 491W class. Having been wounded at Fredericksburg, Joshua Pusey came home to invent paper matches and numerous other ingenious devices, commuting into Philadelphia from his estate on Middletown Road; Joseph Pratt served as captain of the 124th Pennsylvania Infantry, then became a merchant with sufficient resources to leave numerous clocks and gold watches to his children; Charles D. Manley Broomhall grew up in Edgmont, served directly under Joseph Pratt, and returned to become a lawyer and district attorney in Media. In recent years his detailed diary of the battle of Antietam has resurfaced in Connecticut and been published on the internet.100

Civil War prison camp

The women are, of course, much harder than male soldiers to trace from their gravestones to the public record. Sarah Danfield was the wife of Samuel, a Chester grocery store owner and city councilman, each of them represented by a marble stone of equal size, side by side. But Samuel’s 1888 will, while careful in its provision for his “dear wife Sarah,” also speaks for her by saying what he bequeaths to others after her death, an event still nineteen years in the future at the time of his decease; such instruction certainly exemplifies women’s traditional deprivation of voice and will, as opposed to the spiritual equality that the gravestones represent. On the other hand, Sarah Griswold not only crafted a remarkably detailed will before her death in 1874, parceling out household goods among her three children; she also preserved her dowry in the form of “principle of a bond” for $3000 which she held apart from her husband Job, specifying that it should be divided equally among the children when he died. Not co-owner of their 141-acre farm along Chester Creek in Middletown, she was still an agent in family finances.101

But we must conclude with the Pratts and their kin, owners of the Cumberland property and our central cast of characters in this study. Minshall Painter’s “Necrology” offers a valuable report on two of them, both buried in the cemetery. Thomas and Mary Pratt had four sons but left land to only three: what had become of the fourth? Painter’s vignette tells of the risks to life on their apparently bucolic farm: in 1872 Phineas Pratt “came to his death by the bursting of a fly wheel…while at work cutting hay being struck by a piece of flying timber…He was a very ingenious and intelligent young man and he died much lamented.” A more positive ending is given to his mother Mary, whose inability to participate in management of her inheritance had been so keenly felt. Two years before Phineas, Mary Worrall Pratt died “much respected,” and “the funeral was attended by an unusual number of people.”102 The community if not the execution of law could give this woman recognition.

All the Pratt children are buried at Cumberland, within sight of the farmhouse where they grew up. The cemetery offered an inclusive landscape despite the contentions around it. In fact the inclusion extends beyond Thomas and Mary’s immediate family circle, as two additional student case studies from 2003 have led us to realize. Sharpless Worrall, the brother who testified about Mary’s exclusion from her inheritance of the cemetery land, is also buried there along with his wife; as he approached death in 1887, this Willistown farmer overcome any lingering resentments and invested in Cumberland. And so did Joseph Pratt, the Civil War captain. Though in 2003 it was unclear how he was related to Thomas, our dairy farmer and cemetery founder, further genealogical digging has revealed him to be a second cousin, directly descended from the eldest Pratt who had once inherited the land that is today Colonial Pennsylvania Plantation. But Joseph’s descent was illegitimate: his grandfather had been the product of that eldest brother’s youthful misdeeds, and there was no prospect of land inheritance for him or his descendants. Instead grandson Joseph (1834-1908) grew up in Gradyville, became a grocer, and did well in both commerce and military service.103 His fenced family plot and “GAR” emblem at Cumberland—all considerably more prominent than the Quaker-plain gravestones of Thomas and Mary Pratt—are a deserved declaration of pride, status, and family membership.