Tyler Arboretum, less than a mile from Penn State Brandywine, is a 650-acre garden and environmental education center that celebrates the trees and other plants cultivated over half a century by Minshall and Jacob Painter (1801-73, 1814-76), farming brothers whose wealth allowed them to turn from profit-making production to horticulture. But Tyler is also a family farm, its historic house (Lachford Hall) a time capsule that takes visitors back to the brothers’ era and beyond. First built by the Minshall family in 1738, on land that was theirs since 1681, it became the Painter homestead when Hannah Minshall, the only child of her generation, married Enos Painter in 1800.18 Its neighbor in Edgmont, Colonial Pennsylvania Plantation, is a working farm reconstructed with historically accurate furnishings in the twentieth century to bring an earlier time to life. By contrast, Lachford Hall at Tyler Arboretum contains the Minshall-Painter-Tyler family’s actual household goods and furniture as they were left when the last residents departed. Both houses have distinct sections marking growth from one generation to the next. Both are linked to Penn State, the Plantation as Thomas Pratt’s ancestral home and the Arboretum as a hub of activity by his mentors and allies, a place he would often have visited.

The Painters were remarkable in their preservation of words as well as things: in addition to their surviving tree specimens, house, and on-site library, the family kept a vast archive of business accounts, scientific observation, historic reminiscence, letters and diaries, and even school notebooks, all of which are accessible today in the Swarthmore Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore College. In recent years both Tyler and Swarthmore have welcomed Penn State American Studies students to explore these scenes and archives, and what we have to say about the family builds on such discoveries. Though the eminent brothers have always focused our interest, we have also looked at them within a broader network of family members and neighbors across gender and generation.

So we begin with the parents, Hannah and Enos (1782-1838, 1773-1857): she the key to preserving her family lineage, he (an apparent outsider from Chester County, trained as a hatter) the agent of growing prosperity. If they followed the usual courtship patterns of the Quakers, the young people chose each other, but with parental approval as an important framework. Hannah had transcribed the humorous “Advice to Choose a Husband” into her school commonplace book short years before their marriage in 1800: “Please thy parents if thou can/Be sure thyself to love the man.19” As far as we can tell, all apparently gained in this union. Hannah’s widowed father lived in the house another seventeen years but was able to turn over farm management to Enos, instead taking care of his beloved fruit trees and the nearby Quaker burial ground. Hannah gave birth to seven children from 1801 to 1818, far surpassing her mother in reproduction. Enos succeeded brilliantly as a businessman. If we walk into the Painters’ kitchen today, the tools and treasures of this generation are still visible: spinning wheels, a container for cream to rise from milk, an imported Chinese tea caddy. The item that best represents Hannah is a high chair, probably hers in childhood and certainly crucial to her motherhood. A secretary represents Enos: it originally belonged to Jacob but became his own desk; inside it today, as if tucked away from an evening of figuring, is one of his account books of the farm.20

Eldest son Minshall Painter, a family historian as well as scientist and civic leader, offers enough life history of his parents to bring the high chair and secretary to life. Hannah “received for that period a liberal education” but lived within her home sphere, “a woman of exemplary habits and very much devoted to her children.” Enos was not himself “a very extensive agriculturalist,” but instead rented out his lands for tenants to farm, built an enormous stone barn to house his dairy business, and himself focused on increasing land holdings. Soon he had restored the former amplitude of the Minshall estate and acquired more property outside, as well as running a sawmill on the home property and investing in the coal and navigation industries.21

All of these elders, in their respective styles, lived their lives as neighbors and supporters of the Quaker meeting. Grandfather Jacob dug graves in the burial yard, kept interment records, and freely invited strangers home after meeting. Enos oversaw the Quaker school nearby. But when the Separation took place in 1828, the Orthodox accused him among others of actively promoting it. Enos was clearly a contentious person. After a dispute with fellow Quaker Jesse Reece over repair of a fence between their properties, he was finally disowned by even the Hicksite meeting in 1840 and won reinstatement only through appeal to the state Supreme Court.22 His sons, however, opted soon thereafter to leave Quaker affiliation behind. Wife Hannah grieved rather than fought over the division in her community. In 1828, as Minshall wrote, she went with the “more liberal party” but was “most severely tried by being separated from some of her more intimate fellow members who inclined to go with the other party.” She remained a Hicksite, dying ten years later (before Enos’ fence dispute) of a stroke that actually came upon her in meeting. Quaker simplicity allowed for no grave markers. But, as Jacob wrote in a later poem, the fond sons planted a magnolia tree at her burial site, and, “When death released [Enos] after four score years,/ We laid him by her side.”23

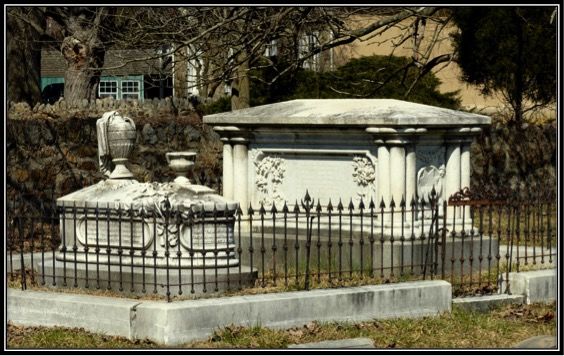

Minshall and Jacob, however, did not in death join their parents at the Quaker burial ground, but instead had elaborately carved stone mausoleums built for themselves at Cumberland, just the other side of the wall from Enos and Hannah. The last lines of Jacob’s self-composed epitaph describe both brothers: “From nature’s laws he drew his creed,/ As taught by nature’s god.” Their devotion to cultivating the natural landscape was based on a larger study of science, begun even before the Quaker division and later controversies took them away from the meetinghouse. Neither brother described the beginning of this fascination, but an entry in Minshall’s diary offers a glimpse of his turn from farming to observing nature. After a day of threshing fields and carrying wood in 1824—with Father (perhaps significantly) absent delivering cider—the young man observed a meteor descending towards the east: “and just before it disappeared it divided into two from the place where it began…and its height from the horizon would make an angle of about 20 degrees.”24 His impulse to measure and record scientific phenomena would long continue; even more than the Quaker Separation or his father’s disputes with the meeting, this was the positive impulse requiring independence from religious doctrine.

Painter brothers' mausoleum

Minshall’s passion for science, assisted by his much younger brother Jacob, is writ large in two Delaware County institutions that should really be visited side by side. At Tyler Arboretum the brothers planted over a thousand trees and plants, many of which survive today amidst the acres that have been planted since their lifetimes. Their goal was scientific observation, not mere adornment. The library that they built in the 1860s was the setting for such study, housing not only books but a mineral collection, microscope, telescope, camera, and printing press.25 All of these things were of a piece with the Delaware County Institute of Science, still open today on Veterans’ Square in Media as a museum and center for what the nineteenth century called the “diffusion of useful knowledge.” Minshall choreographed its activities, gave lectures himself, and left many papers to the Institute. At their fairs, while Thomas Pratt won prizes for his ice cream, Jacob displayed twelve varieties of apples from the Painter farm.26

It is important to realize, however, that the Painter family’s learning did not belong to the two brothers alone. All seven of the children of Enos and Hannah, girls and boys alike, were educated through the secondary level, directly following their mother’s example. In 1836 youngest sister Ann expressed thanks to her chemistry professor at the West Chester Boarding School, and in return he told of his passion for teaching chemistry specifically to women, since it would both serve practical purposes and ascend “the sublimest heights of Philosophy.”27 Jacob was the first family member to attend college, Rensselaer Polytechnic in Troy, New York. But members of the next generation followed suit, as new kinds of higher education became available. Ann’s son William attended the Pennsylvania Agricultural College (Penn State); her niece Helen Barnard, apparently with Ann’s financial support, graduated from coeducational Swarthmore and afterward trained as a nurse.28

In their turn from the Quaker meetinghouse to secular science and knowledge, the Painters were not abandoning community but enlarging it. This was a family of doers. Their sister Sarah and her husband Eusebius Barnard, in Chester County, were the family’s most committed antislavery activists, but at least once a fugitive slave was harbored at Lachford Hall. Jacob’s signature cause was the women’s rights movement; he both attended the 1851 convention in Massachusetts and helped plan its 1852 sequel in West Chester.29 Minshall transferred the family support of Quaker schools to the growing public system; he argued for removal of the county seat to Media and gave the new town its name; he led in making it not only friendly to reform, but itself an act of reform. He was a county leader, both on his own and in league with Thomas Pratt.