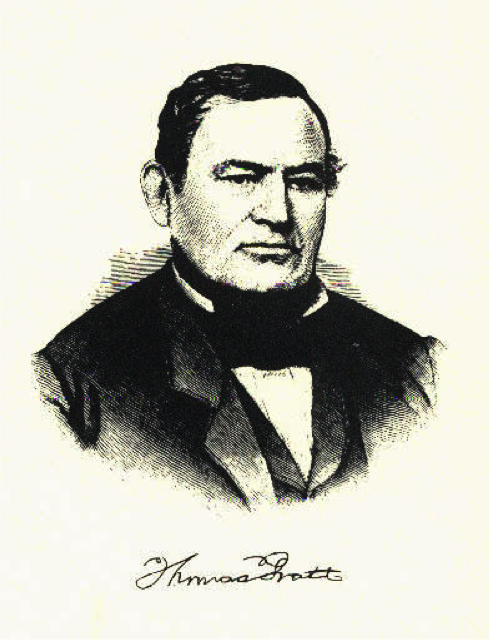

Thomas Pratt (1818-83) grew up on the farm in Middletown that is now Penn State land, assuming full ownership at the age of twenty-one in 1839. As the research of Larry Smythe discovered, Thomas signaled his adulthood in other ways as well that year: he joined the seven-year-old Delaware County Institute of Science, declaring his commitment to knowledge and natural history, and he married Mary Worrall (1817-70), daughter of a nearby farming family with shared roots in Middletown Friends Meeting.4 But the young couple was married by a civil magistrate rather than the Quakers: her family had left the meeting, and though to that point Thomas was still considered a member, his marriage and increasing distance made the Orthodox question his membership in their fold.5 Thereafter the Pratts apparently attended neither religious meeting.

Thomas’s ancestors had come to Pennsylvania in 1682, part of William Penn’s first generation of settlers, and after three years as indentured servants they became landowners. From modest beginnings arose prosperity, through the careful cultivation and transmission of land. Four generations lived on the farm in Edgmont that is known today as Colonial Pennsylvania Plantation, which brings the eighteenth-century Pratt household, fields, and farm animals to life for visiting history lovers. Thomas Pratt, the father of our Thomas, grew up on this farm but did not inherit it. In fact his eldest brother Joseph, who did inherit, may have precipitated the end of the family’s ownership in Edgmont. After fathering an illegitimate son as well as legitimate heirs, he died young and eventually forced the next generation to sell their farm.6 Future Pratt prosperity would lie elsewhere, including with younger brother Thomas.

Established by his parents on another property in Marple, Thomas raised one family there, then as a widower married again to Hannah Heacock of Middletown, becoming owner of the farm she brought with her from a first marriage. This is the land now owned by Penn State. At the remarkably advanced ages of 56 and 52 respectively (if the records can be believed), they gave birth to one child, Thomas, in 1818. Father Thomas died just two years later, and doubly widowed Hannah shouldered the responsibility of raising her young son.7

She did not do so alone, because she had lived her life in a community knit together by blood, religion, and economic interest. Related to the wealthy Minshall family, she reached out to make Enos Painter, the Minshalls’ heir and entrepreneur, her son’s guardian. Painter sold off the land outside Middletown that young Thomas had inherited, leaving the boy with the significant sum of $1828 to make his start in life.8 These families were linked as well through the pre-Separation Quaker community, its meetinghouse directly across the road from the Pratts’ farm, where Monthly Meeting records included Hannah and the child Thomas as members alongside the Minshalls, Painters, Emlens, Yearsleys, Worralls, and Darlingtons. Enos Painter at one point was appointed by the meeting especially to care for the schools that their religious society sponsored. The school that both the Pratt and Painter families chose for their own children was Westtown, the recently founded coeducational boarding school (still in operation today) that led Quaker education regionally in its effort to develop learning and piety in the young.9

Thomas and Mary Worrall Pratt wasted no time in developing their own household and farm operation after marriage in 1839. Mary’s part was the traditional one of reproduction and child raising: two daughters and four sons were born over the decade following. She probably also played some part in dairy farming, since milking cows, producing butter, and even selling the products was considered women’s work.10 The springhouse by the creek was primarily her space, along with her daughters and women servants.

Dairy farming, however, also grew in commercial scale in these years; as one nearby observer wrote, the farmer turned his operation into a “butter factory” and became “his own dairymaid.” The Darlington family, west of the Pratts in Middletown, started by 1840 to gain a national reputation for their butter, eventually sending it even to the White House in Washington by railroad car from a station on their land.11 Thomas Pratt’s specialty was ice cream, shipped by boat from Chester to Philadelphia. As Delaware County historian Henry Ashmead claimed, Pratt pioneered in its manufacture, and “the enterprise proved so profitable as to have induced many others to embark in the business.” At the Delaware County Institute of Science Annual Autumn Exhibit in 1848, Pratt exhibited eight flavors and won first prize for lemon.12 He and his partners also showed an entrepreneurial spirit by advertising. As the ad line proclaimed in the 1860 Delaware County American,

Ice Cream! Ice Cream! Ice Cream! Wm. Beeby having made arrangements with Thomas Pratt, of Middletown, for a constant supply of ice cream during the season, than which there is none better in the market, invites the attention of the public to his saloon on South Avenue, Media, Pa.13

The new county seat was well supplied with the new favorite dessert.

Meanwhile, throughout the 1840s and 50s, Pratt acquired additional property with his profits and joined others in protecting the interests of economic development. He expanded his single farm along the western side of Middletown Road to three, while land inherited by his wife on the eastern side of the road added still more to the family holdings. He bought into the new incorporation of Media in 1849, acquiring property just north of the courthouse and its hub of political power; eventually he retired to a house there. He founded and became president of the Delaware County Mutual Insurance Company, based in Media, and from 1855 to 1858 served as a County Commissioner.14 A wealthy man by 1860, having doubled his assets over the past decade, he could turn his three farms over to three surviving sons and construct a new and elegant parental country house (still surviving today as a private home), across and back from Middletown Road. The marriage of two Pratt daughters to Darlington sons guaranteed their futures and further consolidated family interests. The man who, in 1860, began to develop a cemetery on the eastern side of the road could afford to be generous to his community, though this was also a source of potential profits.15

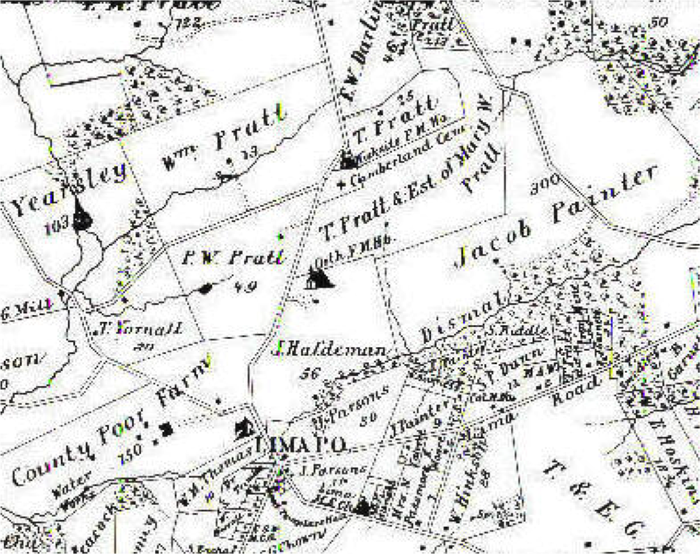

The Pratts and their Middletown neighbors in 1875

But there was internal conflict in this family, conflict having to do with the cemetery property and more. Mary Worrall Pratt’s view of her husband’s career was essentially negative, because she felt unjustly excluded from his profits as a landowner. We can know this from the remarkably detailed court records and news reports of a lawsuit initiated by her two daughters, now both Darlingtons by marriage, after the deaths of their parents. Mary died in 1870 and Thomas remarried in 1874, to Sarah Johnson. Then, when he in turn died in 1883, he left most of the estate to this second wife, at which point the children of his first marriage claimed a right to more of the $30,000 property. As Mary’s brother Sharpless Worrall testified, by the specifications of their parents’ will a substantial amount of capital and land—including the seventy-two acres of which Cumberland Cemetery was part—had been rightfully inherited by Mary but “taken” from her by Thomas Pratt. In dealing with matters of inheritance, Thomas would force Mary to sign power of attorney forms over to him, and she signed. “Thee knows what unkind treatment I have received,” she told her daughters in Thomas’s hearing. “I must sign for peace.” Even when she asked for her profits he refused. “It was a constant source of trouble between them,” eldest daughter Elizabeth concluded, “and during the last years of [my] mother’s life they lived very unhappily.” The 1875 map of Middletown recognizes this double claim, specifying that the land between the two Quaker meetinghouses belonged to “T. Pratt & Estate of Mary W. Pratt.16” Who was right? As we will see further in the section on Women, Thomas Pratt was doing no more than other husbands had traditionally done. Claiming property through marriage was a given of patriarchal society. Yet law and custom were changing, and women’s expectation of independent ownership rising.

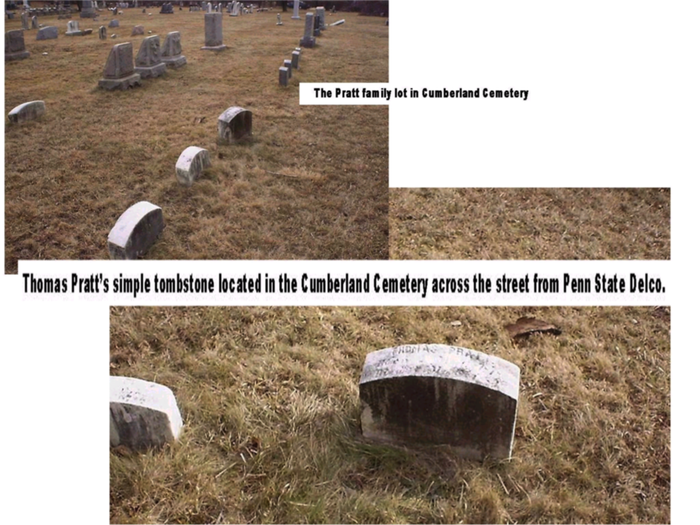

Thomas and Mary Pratt were part of their times in both conflict and accomplishment. Barring the discovery of a new cache of private writing, we cannot know more about this strong-minded wife. Even Thomas’s opinions are largely unstated, his record of accomplishment speaking for itself. But that is clear on the public record. He excelled not only in capitalism but in the benevolent social developments that it could make possible. Though disaffiliated from the Society of Friends, he translated its strong value on social justice and progress to public form. He was an Abolitionist and, by 1860, a Republican. Service on the Middletown school board acted upon the Painters’ Quaker commitment to education in the broader sphere of secular society. The movement against abuse of alcohol drew his strong support, and from 1850 on he served as a manager of the Charter House, a temperance hotel in Media. In 1859 he helped found the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children, becoming a life member of the school in Middletown known today as the Elwyn Institute.17 And his establishment of Cumberland Cemetery a year later should be seen as part of the same public service. We have to accept the irony that it was on land that he took from his wife without her consent. There they are buried side by side, their children and neighbors around them.