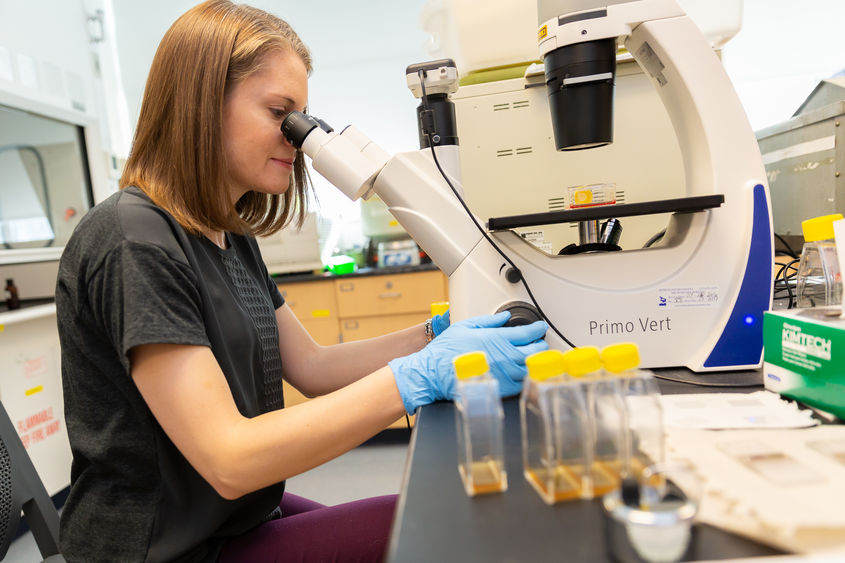

Megan Povelones, assistant professor of biology at Penn State Brandywine, is researching the behavior of parasites in their insect hosts.

MEDIA, Pa. — Married couples generally don’t end their day with dinner-table conversation about parasites and mosquitoes — unless they are researchers whose individual areas of focus present a unique opportunity for collaboration.

That was the case for Megan Povelones, assistant professor of biology at Penn State Brandywine, and her husband, Michael Povelones, assistant professor of pathobiology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

“I was looking at Crithidia fasciculata, a single-celled parasite, and I became interested in this phenomenon where they would develop an adhesive form that would stick to my flask,” Megan Povelones explained. “Related species of parasites that I had worked with in the past wouldn't do that, and it raised the question of what signal is telling them to stick.”

“And then I learned they were a parasite of mosquitoes. My husband at Penn works on mosquitoes and how their immune system affects their ability to transmit various diseases. He was curious about this mosquito parasite,” she added, “so we just had a lot of talks in the evening.”

The researchers decided to initiate a joint project to try to identify genetic factors associated with the adherent form of the parasite versus a non-adherent “swimming” form. This is important because related, disease-causing parasites also adhere to insect tissue, and that adhesion is required for the parasites to be transmitted by those insects to humans.

The results of their study were recently published in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

The parasites used in the study, which were grown in Brandywine’s biology lab, don't cause disease in humans, but they are closely related to parasites responsible for the human diseases African sleeping sickness, Chagas disease, and Leishmaniasis.

“Something these parasites have in common is that at one point in their life cycle they have to adhere to an insect tissue, but they are very difficult to study in the insect,” Povelones said. “But then I thought, here we have an organism that will do the same thing or what looks like the same thing on a flask. So that means you could just grow up tons of them in a flask and study that adhesive structure outside of the insect. And then when we decided to go in and infect the mosquitoes, we could get huge numbers of parasites growing as adherent cells in the mosquitoes as well. And those infections were very easy to create.”

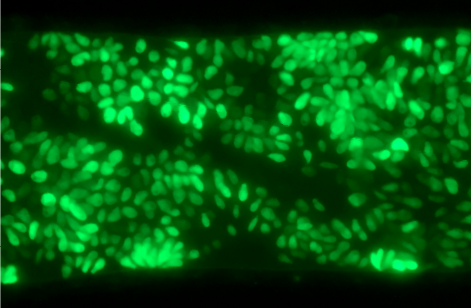

At Brandywine, the cells were prepared, including adding a green fluorescent protein that would make the parasites easy to see in the mosquito tissue. The parasites were then transported to the University of Pennsylvania, where they were added to sugar water that the mosquitos drank.

The researchers then isolated samples to determine genome-wide gene expression patterns in cells grown either as adherent cells, as swimming cells, or in the mosquito. They analyzed this data to look for patterns and genes associated with adherence. This was the first such analysis conducted in C. fasciculata, and the authors collaborated with researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Washington in Seattle who had produced the draft genome sequence for these parasites, which was essential for this approach to work.

“If we can understand more about the factors that govern transmission of the parasites and these insect developmental stages, we can hopefully have some way to target those stages and decrease transmission rates,” Povelones explained.

Povelones enjoyed the opportunity to work with her husband on the project.

“It definitely was interesting to be able to collaborate with someone who I know really well and to be able to spend more time together, even during the workday,” she said. “Of course, having two principal investigators, sometimes there were differences of opinion. We have our particular styles of the way we like to do things. But it was helpful that I was the parasite expert and he was the mosquito expert. It was clear where everybody's expertise was.”

Several Brandywine students benefited from the experience as well. They assisted with the cell preparation, visited Penn’s lab and insectory, and attended lab meetings and seminars. Povelones hopes to continue student involvement with the research.

“This was a really fun project and I think it is a really interesting organism,” Povelones said. “There's lots of novel biology to be discovered and a lot of that biology is going to be relevant for other organisms as well. So I think there’s a lot more to do, and I hope the project continues."

For more information about Megan Povelones’ research at Penn State Brandywine, visit https://sites.psu.edu/bwtryps/.