Joshua Phillips, assistant teaching professor of communication arts and sciences.

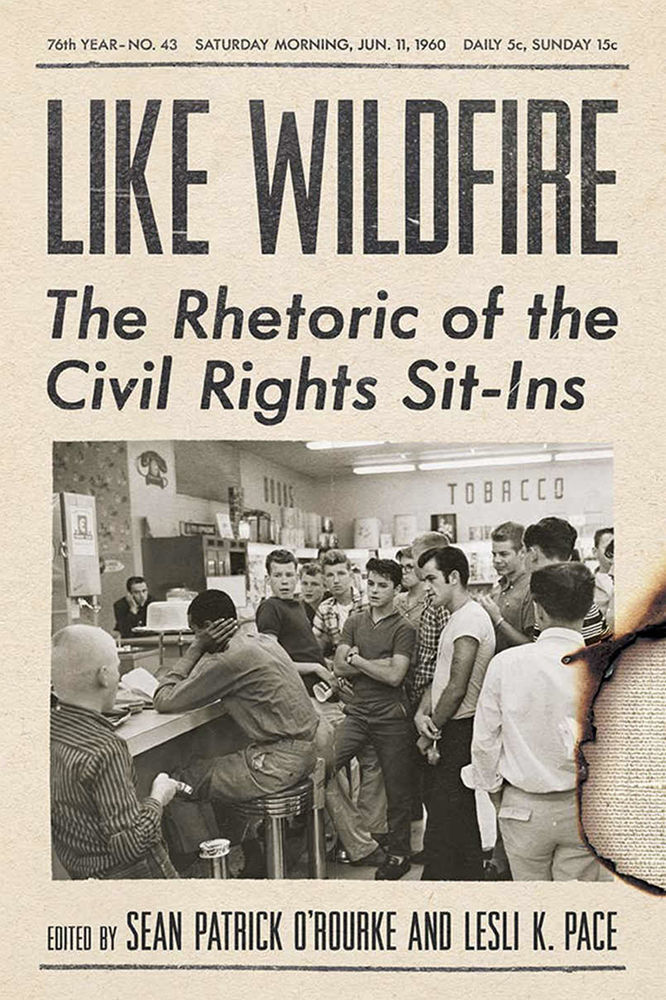

MEDIA, Pa. — Joshua Phillips, assistant teaching professor of communication arts and sciences at Penn State Brandywine, recently wrote a chapter for “Like Wildfire: The Rhetoric of the Civil Rights Sit-Ins.” The book, a collection of essays from leading scholars, seeks to clarify and analyze the power of civil rights sit-ins as rhetorical acts.

“When many people think about the civil rights movement and the sit-ins, they usually only think about the Woolworth sit-ins of the 1960s in Greensboro, North Carolina,” Phillips said. “This book documents sit-ins that were happening all over the country as early as the 1930s. It looks at how various organizations employed different rhetorical strategies to integrate public spaces.”

Phillips’ chapter, titled “Lunch Counters and the Public Sphere: The St. Louis Sit-In as an Emerging Counterpublic,” looks at the work of the Citizens Civil Rights Committee and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to integrate the lunch counters at the Stix, Baer and Fuller department store in the 1940s. Phillips explained that this work occurred within “the shadow of the Supreme Court’s ruling on Shelly v. Kraemer, which said that housing developments could not discriminate by mandating that only ‘white people’ were allowed to buy homes in certain areas.”

Several years ago, the editors of “Like Wildfire: The Rhetoric of the Civil Rights Sit-Ins” approached Phillips about contributing to their book at a conference. They were familiar with his previous work surrounding race, intercultural communication and rhetoric, and knew he would be an excellent fit.

“What I’m most interested in is making sure that all voices are involved in public policy conversations,” Phillips said. “If you look at my book ‘Homeless: Narratives from the Streets,’ it’s all about including the voices of people who are homeless in policy discussions. With the civil rights movement, it was all about making sure that all voices were involved in the discussions that lead to important reforms.”

From start to finish, Phillips said his chapter took approximately one year to complete. He tracked down many historical documents throughout the research process, some of which included interviews kept in St. Louis archives, as well as fliers that protesters used to recruit and instruct other protesters.

“This book gives us a better understanding of how much work and time went into the civil rights movement,” Phillips said. “In many regards, the protests we see today are an extension of that. The civil rights movement was a decades-long process that included millions of people all over the country. I think it's important that people realize that. Issues of equality and justice don't just happen overnight because of a few people. It's a long process that requires effort from everyone.”